Luxury is being redefined by unprecedented socioeconomic change. The classical view of luxury seems to be fragile in the face of new technologies and aspirations. Complex polarities are emerging between demographics, with each demanding their own personalized, bespoke experience. What of ‘luxury’ is reliably unchanging, and what is emergent that brands can take advantage of?

Keywords: #luxury #sophistication #art #wealth #gucci #richemont #cartier #design #illustration #thesis

Part I Sophistication

The word ‘sophistication’ is tied to our idea of luxury, meaning ‘refined’. The semantics of this word are complex, primarily because it’s meaning has changed multiple times throughout history. In ancient Greece, Sophistry referred to the insight and wisdom of poets and philosophers[1]. It then became a derogatory word, meaning to ‘mislead’. And up to the 18th century the word was used in the same sense, as something misleading and decadent. It was only until the 19th century that ‘Sophistication’ equated to refinement, and something to be admired.[2]

The constant theme is that sophistication creates limited access and allusive knowledge[3] – and this is always to the excitement of insiders, and annoyance of outsiders. This demarcation explains why the idea of sophistication has often been contentious.

This is worth bearing in mind, because emergent demographics – Generation Z, among others – have been sensitized to societal inequalities, in all forms.

Yet, I propose that there remains an unspoken ‘hierarchy of Sophistication’, in spite of any aspirations to equality. And if brands were aware of this hierarchy, and where they fit in, they would be able to refine their strategy, confidently navigate shifting trends, and come out on top, as other brands miss-judge their place.

When it comes to luxury, a product embodying ‘Sophistication’ requires two things: conspicuous wealth, and understatement. These are the two ends of the tightrope that define the hierarchy of Sophistication; if one end goes slack, sophistication breaks down. I.e. if there is merely the context of conspicuous wealth, then the feeling is brash and arrogant. And if something is merely understated, then the feeling is naive and apologetic.

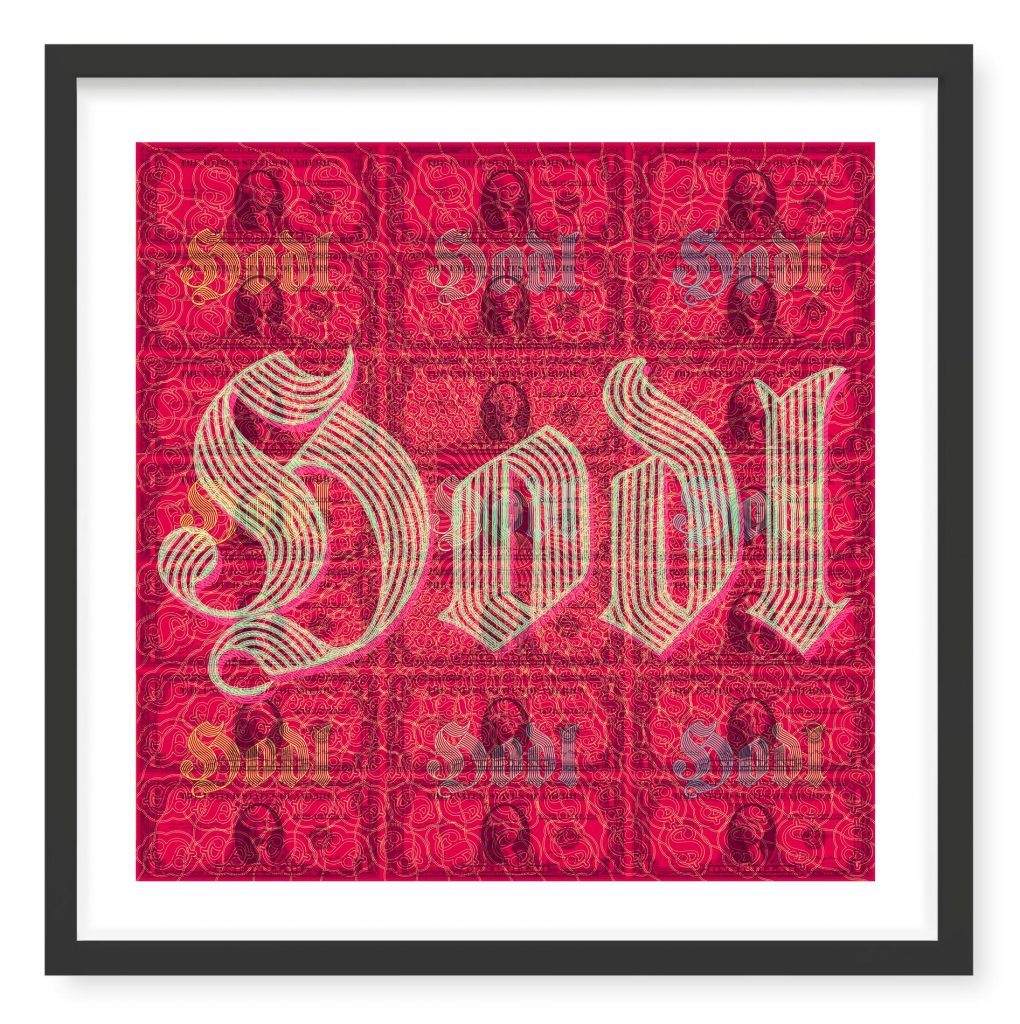

When both conspicuous wealth and understatement are perfectly harmonized, we get to the pinnacle of the hierarchy. And there, we find Art. Art has zero material utility – you can’t wear it, eat it or burn for fuel, so Art is 100% reliant on the context of conspicuous wealth. This also means that art must, at every opportunity, balance this out with understatement, in order to preserve its subtle refinement. And the more conspicuously wealthy, the greater the understatement has to be.

This has a few interesting consequences. First, it leads the ‘art outsiders’ – sections of the public, tabloid newspapers – to confusion and outrage. How can “something I could do/my cat could do” be put on pedestal and worshipped?

It also means that Art has the freedom to self-consciously play with these unique dynamics. Robin Altar’s work, for example, is a literal ode to art’s special place in the luxury hierarchy: Ketchup bottles made of Travertine and Carrara marble, or Doc Martins made from highly polished stone. Altar’s work is an understatement dance, wrapped in the luxuriousness of its finish and materials.

Other luxury goods do not have the same freedom as art. This is because they still have to bow to utility – they are to be worn, driven or hold things. There are rules of use and comfort, and if a luxury product puts ‘art’ before ergonomics, it shaves off its value – unless, of course, it is re-appropriated as art, and is reincarnated at the top of the hierarchy.

But the instances of a luxury product re-appropriated as art is rare. Why? Simply because art must appropriate understated things to balance out conspicuous wealth! Art prefers to take the throw-away and transform it.

Of course, at the high-end, an artist may work with precious metals and stones, or collaborate with a luxury brand to produce customized limited editions. For the latter, the exchange makes sense – the artist forfeits a little conspicuous wealth to be slightly more accessible, and the luxury brand forfeits some understatement for a taste of Art’s affluence. It’s a fair exchange, and Sophistication remains in balance.

That being the case, what should we make of Gucci’s ‘dirty’ Screener leather sneakers, with a ‘distressed’ look? It is interesting that the criticism for Gucci’s shoes is similar to the outrage from ‘art outsiders’, who bemoan the high price tag for “something I could do myself”.

According the Hierarchy of Sophistication, Gucci is walking a risky path. It must kowtow to utility, but it is toying with understatement. Of course, there is nothing new in products with an attractive ‘distressed’ look, but old, worn, dirty sneakers cross over from ‘vintage’ into ‘poverty’, and this generates brand dissonance.

This is an example of where imbalance between conspicuous wealth and understatement cause sophistication to go slack. And while shock and criticism is an asset in Art (because it acts as a foil to its conspicuousness), it can be detrimental to a tool – such as shoe – especially in an atmosphere of sensitivity to class inequality. In this case, and the case with Golden Goose (criticised for a pair of trainers that looked like they had been taped-up with duct tape), the brands were accused of “commercializing poverty”[4].

So, this is really no different from Ancient Greece. The Sophists – the poets and the philosophers – had brilliant insights, but when they overstepped their boundaries in using rhetoric to win arguments, they were accused of deception. In the same way, when a brand oversteps its boundaries by playing with understatement and conspicuous wealth when it’s place in the hierarchy doesn’t permit to do so, it too will be accused of duping its followers.

Sophistication is simply the coincidence of conspicuous wealth and understatement. The solution is for brands to be acutely aware of these dynamics, and to know exactly how much liberty they have to play within them – which is determined by where their brand and function sits along the hierarchy of Sophistication.

The question is, what if ideals of accessibility and equality become a reality? If there were no insiders and no outsiders, just where would Luxury be? How would sophistication be possible, or even desirable?

This poses a massive headache for Luxury. This is expressed by Johann Rupert, chief executive of Richemont:

“This is really what keeps me up at night… Because people with money will not wish to show it. If your child’s best friend’s parents go unemployed, you don’t want to buy a car or anything showy.”

Obvious signs of affluence is driving the need for understatement. The dynamics of Sophistication don’t go away, but they dictate the strategies that Luxury must deploy to stay alive.

In Part 2, I’ll ask where Luxury can go for safety…

[1] Mark Backman (1991), “The Roots of Our Sophistication”, Sophistication, Ox Bow Press, ISBN 978-0-918024-91-6

[2] Deborah Longworth (2 Sep 2010), “Sophistication: A Literary and Cultural History”, Times Higher Education

[3] Attardo, Salvatore (1994). Linguistic theories of humor. Humor research. 1. Walter de Gruyter. p. 216. ISBN 978-3-11-014255-6. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

[4] Lucia Binding, https://news.sky.com/story/gucci-criticised-for-selling-dirty-trainers-from-615-11671849

[5] https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/louis-vuitton-and-guccis-nightmares-come-true-wealthy-shoppers-dont-want-flashy-logos-anymore/2015/06/15/e521733c-fd97-11e4-833c-a2de05b6b2a4_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.0c6331551531